by Karen Yvonne Hamilton, 2025

Excerpted from Lostmans Heritage: Pioneers in the Florida Everglades by Karen Yvonne Hamilton

All content here is copyrighted. Please give proper credit if sharing and/or referencing.

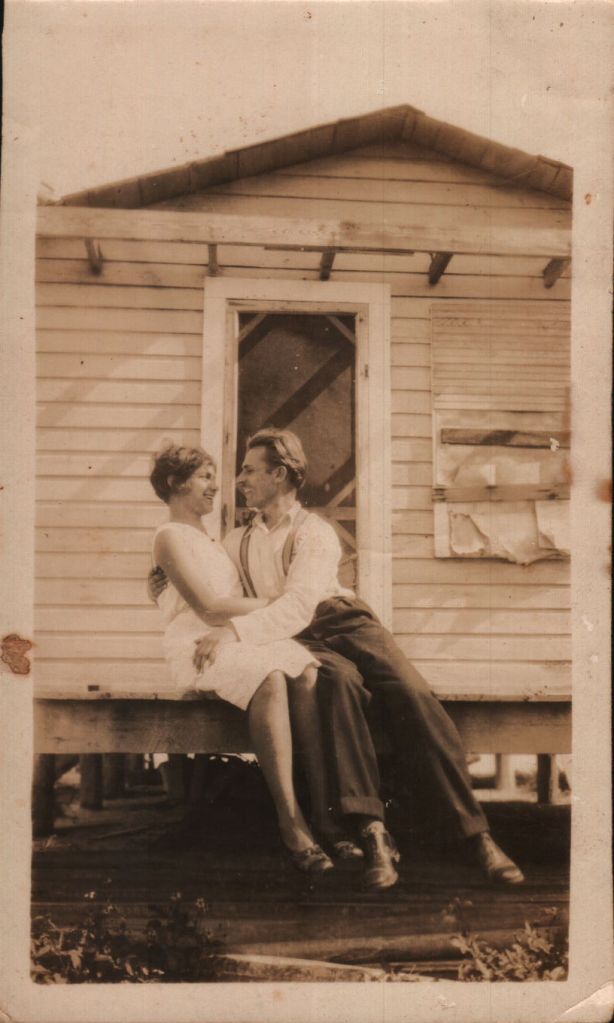

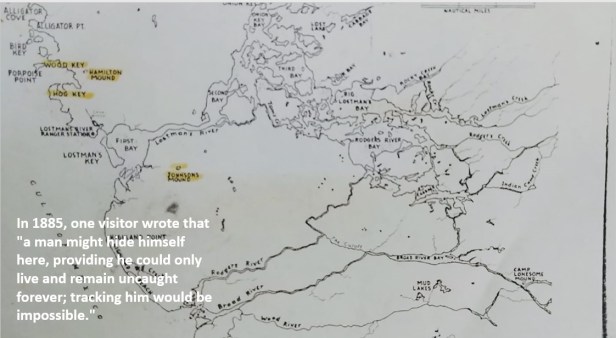

The sons and daughters of Richard and Mary Appolonia Hamilton knew no other way of life than the one they were born into on those islands. The white sandy beaches, oyster beds and coral reefs, mangroves and sawgrass, Spanish moss, and orchids was the only home they had ever known. Papa Richard taught them well. The Ten Thousand Islands was their hidden paradise, and for the majority of the years they lived and raised families there, the only access to their paradise was by sea. They knew their way around the islands as well as any Seminole guide.

To come upon one of their homesteads in the mid-twentieth century was to encounter a scene that was anachronistic, a blast from some long past tribal abode. More often than not their humble lodgings consisted of a houseboat and several skiffs for fishing and navigating between islands. On the beach you would find all manner of animal skins being dried in the sun: alligator, panther, deer, rabbit.

On Gene Hamilton’s homestead, one reporter detailed the shell mound where Gene had built his crude but functionable house. He describes the hanging baskets of fruit hanging in the trees and the profusion of trees – palms, live oaks, buttonwood, mahogany, and cypress dripping with Spanish moss and air plants.

Still, there were drawbacks to living on the islands, but the residents found ways to deal with them. One paper reports, “Swamp angels were an ever present annoyance during the warm season, but they carried mosquito bars wherever they went, built crackling fat-pine fires to ward off the molesters at night and dabbed kerosene on their skin during the day to discourage the insidious “no-see’ums”.

Changes were coming though. In 1922, the Tamiami Trail was completed and opened up the islands to even more tourists, explorers, and entrepreneurs. Shortly thereafter the United States entered the Depression era. The Great Depression was a devastating period for many Americans. For roughly ten years, between 1929 and 1939, the country struggled to regain its footing in a shaky world. Banks failed. Savings were lost. Families watched as their homes were repossessed, and they took to the road, living vagabond existences. Children begged for food. Countless numbers of Americans died from illness and starvation.

The pioneers of the Everglades and their descendants however had little need for money and plenty to eat. Despite some inconveniences like mosquitos, alligators, and the occasional hurricane, the residents carried on with their lives as usual. They were surrounded by everything that they needed. My father, Ernest, told me, “I don’t recall ever going hungry. The adults were strict, but us kids were happy.”

I will let a few of the Richard’s descendants describe what it was like growing up there, themselves having been born and raised there in the decades before the National Park Service took over. The following memories and tales are from letters and interviews with several family members.

Shelter

Ernest Hamilton, youngest son of William ‘Buddy’ Hamilton, grandson of King Gene

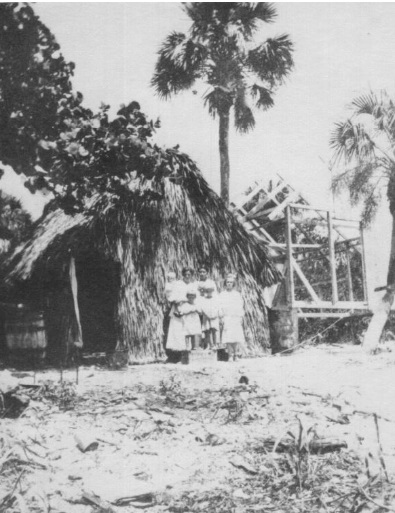

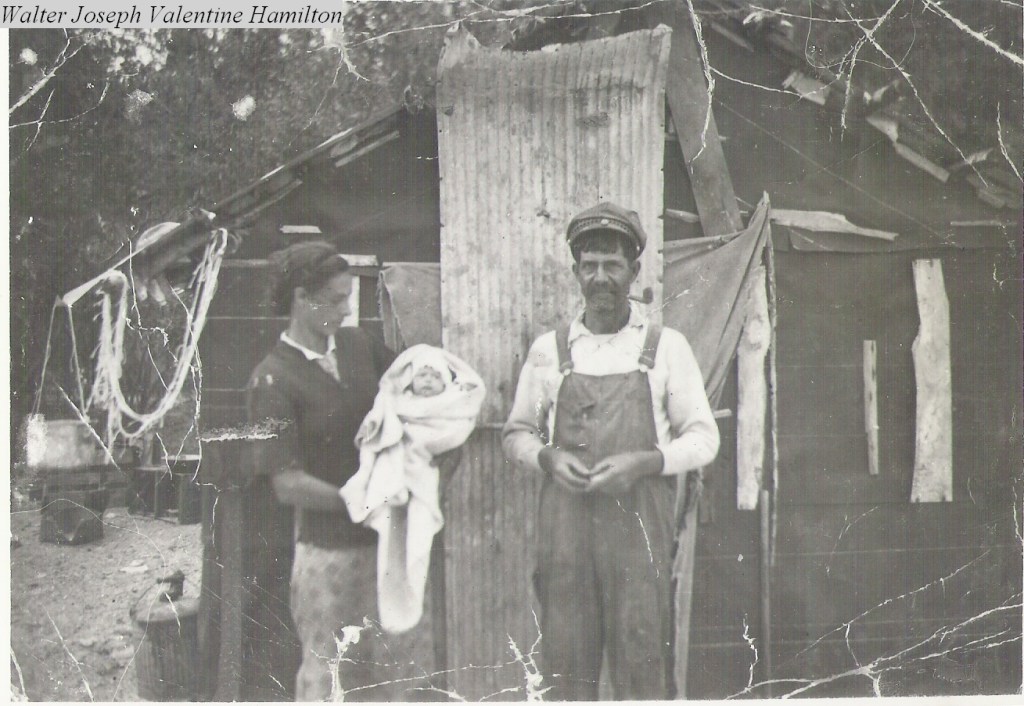

“The housing was pretty much the same anywhere you went. Unpainted boards, usually tongue and groove, maybe covered with black tar paper on the outside to keep the rain out and usually unfinished on the inside with 2 x 4s and single tongue and groove boards exposed. The inside may have partitions of wood or just simply material hung to provide separations. Until a permanent house could be constructed, folks lived in huts with palmetto tops (thatched roofs).

Windows were, for the most part, made of glass, but until glass could be brought in, people used some sort of treated cloth to cover the opening. Most places had screens in the doors and windows to stall the entrance of mosquitoes. The mosquitoes were always fierce, and sleep was facilitated by mosquito nets and by the burning of a smudge pot that produced smoke. It consisted of black mangrove charcoal and dirt. This material was placed inside the top of a coffee can or a bucket and ignited. The mosquitoes were still there when I visited in 1987. We used Crown Royal to fend them off!

Floors were most often made of wood with no covering at all. The kitchen floor may be covered with linoleum. There was no electricity. Lighting was accomplished with kerosene lamps, candles, or gas lanterns. Most times activity inside virtually stopped after sundown. Activities after dark usually occurred outside around an open fire. The big thrill were the ghost stories told around those fires.

All toilets were outside, usually some distance from the main house. At night chamber pots were used and emptied in the morning. The outhouses were also constructed with unpainted wood. The seat was made of flat boards with a hole or holes in it. Lime was periodically poured on the refuse to accelerate deterioration. Sears & Roebuck catalogs were available if someone had been to town recently. The pages were used for toilet paper. Many times, there was not even an outside privy. Living by the water provided a natural sewer.

We lived in many places, back in the 1930s and early ‘40s. One place we lived at several times, usually during the school periods, is in the center of my mind in memory. It was a little piece of high ground along the banks of the Caloosahatchee River, near the small settlement of Iona, Florida. We had a house, smoke house, small cabin, an artesian well, and of course, an outhouse, complete with Sears & Roebuck catalog. I believe in those years, fishermen were squatters, wherever they found an empty place they just moved right in.

At another time we lived in a house built over the water near Turkey Key, still down in the Islands. One day while I was contentedly playing with my boats underneath the house, I was interrupted and forced to come topside to have my picture made. I was mad. I had to pose with Junior and Francis. The picture hangs today in my office at home. It will give you an idea of what the houses looked like. I’m glad they forced me. I look at that picture on occasion and pause to remember the good old days. In 2002, I took pictures of the remains of that old house – black, rotted poles jutting out of the water, far out from the island it had once been near – the product of time, hurricanes and erosion.

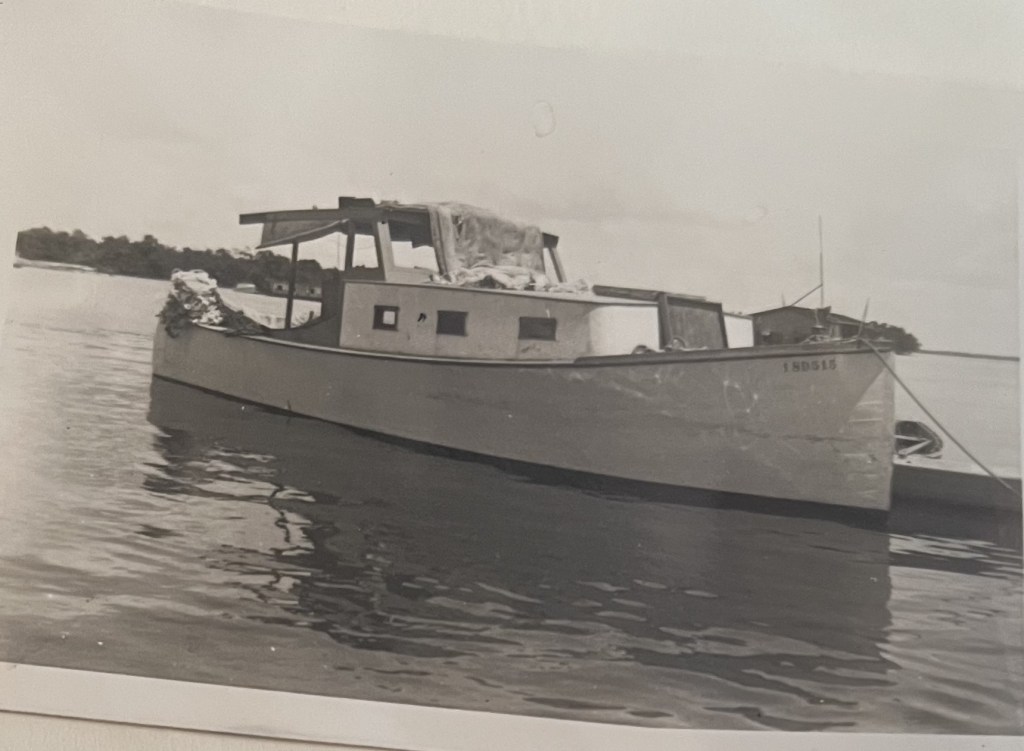

Down in the Ten Thousand Islands we lived for a while on a lighter. A sort of houseboat, except this one also had a fish house on it. Bill Parker, my stepfather, tended the fish house. He would dock up at various places from time to time, and the fishermen would come to him with their catch. Once he had a decent load, he’d head for the main fish house at Chokoloskee or Everglades City.”

William Hamilton “Junior“, eldest son of William ‘Buddy’ Hamilton, grandson of King Gene

“My people were fishermen. We traveled and moved to many different places. Wherever the fish were running, we went. We lived in a lot of unpainted shacks and tarpaper sided house or lived right in the boat.

One of the places we lived in the late 1930s was Mormon Key. At Mormon Key there were five houses built over cisterns. Four were in a single line near the beach and the one we lived in was sitting on the top of one of the Indian mounds, sitting back about 150 feet from the beach. In other words, pretty close to the middle of the Key.”

Paul Gomes: Son of Salvador Gomes and Rosalie Hamilton, grandson of King Gene

“Probably fifty percent of the housing was lighters. And the other was shacks and stuff on different islands, everybody picked a different part of the island.”

Lostmans Heritage: Pioneers in the Florida Everglades follows the author’s journey as she searches for her ancestors from the slave country of Savannah to the wilds of Ocala and Arcadia, Florida, and deep into the Florida Keys and Everglades. This true story begins with Hamilton’s ancestor, Richard Hamilton, who was first introduced to the world in Peter Matthiessen’s novel, Killing Mr. Watson. Hamilton’s research follows Richard, a former slave, and other Everglades residents to the ending of an era when the National Park Service took over the islands. Along the way Hamilton uncovers secrets and stories, polygamy, bootlegging, fist fights, murders, gangsters, killers, and tales of tomahawks and missing schoolteachers. The Everglades was not a place for the average man at that time. You did what you had to do to feed your family.

FLORIDA KEYS HISTORY FACEBOOK GROUP: Consider joining our group for more on Florida Keys History.

FLORIDA EVERGLADES HISTORY FACEBOOK GROUP: Consider joining our group for more on Florida Keys History.