Karen Yvonne Hamilton, 2024

On May 11, 1865 Justin Everett Knowles married Jane Ann Hopkins in Key West. Jane was 18 years old. A few months after their marriage, Jane Ann’s parents, James Hopkins and Frances Elizabeth Harriede Hopkins contracted yellow fever. They died on the same day, August 11, on Knockemdown Key. They left behind four children ranging from 12 years old to five. Jane Ann took into her own household her older siblings, Charles and Henrietta. She and Justin may have also taken in the younger boys, James and John.

Yellow fever is now known to be spread through the bite of an infected mosquito. According to the current definition by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), “Illness ranges from a fever with aches and pains to severe liver disease with bleeding and yellowing skin (jaundice). Yellow fever infection is diagnosed based on laboratory testing, a person’s symptoms, and travel history. There is no medicine to treat or cure infection” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Life on the Florida Keys had to have been hard enough just trying to provide food and shelter amidst turbulent weather and isolation from medical care and other people. James and Frances Hopkins would have had no help as they lay dying of yellow fever. In the extreme southern areas of Florida, the threat of yellow fever lasted all year round (Huffard, 84). As Key West had a port that brought goods from the tropics, it also brought yellow fever. And from there and other southern ports, an American epidemic was born. Life in those times were fraught with fear, grief, treatments that were often as horrendous as the virus, quarantines, collapsed economies, and crippled transportation.

Life in the 19th century was clouded with the ominous threat of ‘yellow jack’. The south in particular saw more cases than any other part of the country. The worst outbreak came in 1878 to the Mississippi River Valley with over 120,000 cases recorded and 13,000 to 20,000 deaths (“The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878”). While contracting the virus did not always mean a death sentence, contractors of it did experience hideous symptoms such as acute fever, yellowing skin (thus the name Yellow Fever), black vomit, and internal bleeding that caused bleeding from “every orifice” (Huffard, 83).

Treatments and ‘Cures’

Yellow fever raged through Key West as early as 1862. Key West physician, Dr. Joseph Porter reported that many of the local cures for yellow fever were as deadly as the disease. One such treatment is described in The Journal of Practice by Surgeon Steward Plummer of the USS Honduras:

“Samuel D. Holt, acting third engineer, age 27, ushered in Aug. 8, 1863. Fever started with a chill and colic. A week previous given dosages of compound spirits of ether and whiskey. Ensuing day, fever strong and intense pains in the head. Gave calomel and rhubarb, 15 grains each. Cold applied to head. Treatment afterwards consisted of acid drinks, liquid potasse citrate and occasional one ounce of castor oil. Thirty drops of laudanum and six drops of turpentine to check the bilious discharge.” The report does not share whether Holt survived the treatment or the yellow fever” (Diddle, 21).

In an 1887 handwritten diary entry, we get a sense of the physical toll on one suffering from the yellow fever.

Handwritten diary of E.E. and E.B. Johnson and Yellow Fever

A short sketch of the origin of the Yellow Fever epidemic 1887

“In the spring of 1887 yellow fever broke out in Key West and after some months was controlled and suppressed. Considerable alarm was manifested in Manatee and a quarantine put on against Key West and Cuba. It was at this time that father remarked that he could nurse the whole of our family through a scourge of the fever, having had opportunity to learn the best treatment from Key Wester’s he had utmost confidence in his ability and I do not doubt that he could have made good his assertions had they occurred as expressed.

“Egmont Key was made a Y.F. hospital and all cases were transported there. It was during Sept Oct that reports were circulated regarding sickness in Tampa but through reports made by physicians and others it was passed current as Dengue Breakbone and other fevers. And thus no undue alarm came to Manatee. At this time we were keeping store in the “Progress” building rented off J.W. Garlle (sic).

“During the year 1888, father had a spell of ‘sciatia (sic)’ which was very sever (sic). This was the 1st and only time I ever saw him in bed until the Y.F. came. Friday I stayed from school to run the store. Page missing “of violent pains in his legs and arms and head, a scorching fever, tossing and rolling in bed almost unable to control himself. Not suspecting anything like Y.F. none of us became alarmed and as he refused to call in a physician we did not consider anything alarming. By his instructions we prepared such medicines as he called for which had a good effect, accompanied by the careful nursing and attention of mother.

Visiting friend came in and from description called in Dengue fever. On Friday the day following I was attacked with the same severe symptoms, the most violent pain I ever experienced, during the whole night I lay tossing and pitching, the railing of the bed was a comfortable companion to ease pain. Pan after pan of cold water was vainly used to cool my heated head. On Saturday night Rollo and Emony sought the bed in the same manner we had done. It was reported also that Rev. J.R. Crowder and Dr. Driscol were sick in bed.

For several days I remained in the same room that father occupied. I became very restless and insisted upon a doctor being called for my self. At this moment Pilot and Leffingwell were passing and as I preferred … (page ends here).”

Notes made in the margin of this last page:

Dr. Leffingwell could not name the fever. Dr. Heher Smith of Egmond U.S.S. confidentially called it Y.F. but found a dispute in Dr. Pelot, and thus it remained an unsettled matter.

All these facts were not agreed upon until the year after when the fever came again.

J.C. Pelot (was the) only doctor in Manatee. (Dr.) J.B. Leffingwell (was) in Bradenton.

(Manatee County Public Library, “Handwritten diary of E.E. and E.B. Johnson and Yellow Fever, page 60).

In October of 1878, a steamboat traveled down the Mississippi carrying supplies, donated items, and the mail to towns along the route. The mailbags were “…suspended from and around the edge of the boiler-deck and thoroughly saturated with turpentine three times a day.” The crew also used chloride of lime around the boat. Upon arriving in Memphis, the captain reported, “Memphis looks like a grave. The wharves are almost entirely deserted. Occasionally a small dray and a few negroes could be seen, but otherwise it all looked like death. The city looks mournful in the extreme, appears gloomy and desolate, with a funeral pall overhanging it and dread disease lurking in the shadow.” Several crew members died of the fever, and their bedding and clothing “were burned, and chlorine gas evolved in the room to thoroughly fumigate and disinfect it.” The crew would also use “burning sulphur and alcohol” to fumigate the entire boat.

As the crew took in mail from some places, they would disinfect it with turpentine even though the townspeople had already “carefully fumigated with sulphur every night” every piece of mail. Despite the harrowing conditions and threat of infection, the crew of this unnamed steamboat was able to provide aid and assistance to many towns and people suffering from yellow fever (“Report of the expedition for the relief of yellow-fever sufferers of the lower Mississippi”).

The New York Times reported correspondence from Key West regarding the conditions and movements of soldiers and sailors in 1862. The article includes a recipe for curing the fever:

KEY WEST, Fla., Saturday, Sept. 13, 1862.

“There seems no abatement of the yellow fever in our midst, and new cases continue to take the places in the hospitals made vacant by the deaths constantly occurring there. Some of them are so filled with patients that it is quite impossible that they shall receive all the care and treatment that is necessary.

The deaths at this Hospital average three daily out of about forty-five patients. Our Northern Doctors are not easily induced to adopt the practice which has, from long experience, become universal here and elsewhere among yellow fever, of giving in the very first symptoms of the disease, a large dose of calomel — say fifty grains — which in most cases, when accompanied by a hot mustard bath producing perspiration, checks the fever, and the patient recovers. Some of our Navy Surgeons give but eight or ten grains of calomel; their patients full away, and, as a last resort, they are sent ashore to the Marine Hospital, where most of them soon die (OUR KEY WEST CORRESPONDENCE).

Call for Aid & Heros

The south called for aid from the world. And the world responded. People from all over sent supplies and money to the sufferers of the yellow fever epidemic.

“The children are very busy in making preparations for their Fair in behalf of the yellow fever sufferers at the South, which is to come off on Friday next. They have had printed one or two hundred tickets of admission, at ten cents each, and are endeavoring to find purchasers for them. How many persons may be induced to come from the town is problematical. A lady, boarding at Mr. Cole’s, has generously expended sixty dollars in purchasing articles for the tables” (Garrison, 1878).

“Historical marker in Key Largo – Monroe County, Florida”

Sign text read: Convent of Mary Immaculate (1878) Built by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, a Canadian Order which first established a school here in 1868. Designed by William Kerr of Ireland, of Romanesque style with dormered mansard roofs and central tower. In the Spanish-American War, the sisters offered their services as nurses and the Convent to the Navy as a hospital, and rendered devoted service to the wounded and yellow fever victims. F-78. Florida Board of Parks and Historic Memorials. 1962.

Heros were in short supply, but accounts of those who sprang to the aid of their fellow man were everywhere. In one story, a madam in Memphis opened her brothel to the sick and dying. “The keeper of a house of ill-fame on Gayoso Street dared the loss of ‘business,’ dared the desertion of her place by all but one its inmates, to nurse faithfully to the end one who was to her a comparative stranger, but whom chance had brought plague-stricken to her door” (Dromgoole). Annie Cook was the name she was known by; her real name was unknown. In 1873, Annie opened her house to those stricken with yellow fever and nursed them until the end. She died of the fever herself in 1878.

A group of women of Louisville wrote a letter to Annie in August 1878:

“Madame Annie Cook, Mansion House, Memphis, Tenn.:

Dear Madam: This morning’s paper announces that you have opened your house to the sick of Memphis, and that you are ministering to their wants personally. An act so generous, so benevolent, so utterly unselfish should not be passed over without notice. History may not record this good deed, for the good deeds of women seldom live after them, but every heart in the whole country responds with affectionate gratitude to the noble example you have set for Christian men and women. God speed you, dear madam, and, when the end comes, may the light of a better world guide you to a home beyond. From the Christian Women of Louisville, KY.

(Dromgoole, excerpts from “Dr. Dromgoole’s Yellow Fever Heroes, Honors, and Horrors of 1878″)

Travel Restrictions & Quarantines

As quarantines became more and more common, residents of towns rushed to cross city borders to avoid being trapped in the city. When quarantines were set up, guards were posted to keep people in (or out). Those who carried ‘immune’ cards stating they had already had the fever and survived, were allowed to move somewhat freely. Detention centers were established in almost every infected city to quarantine those who were infected. In Key West, these ‘camps’ were often ships or boats that were set up as medical centers. Those who were sick with the fever on the Florida Keys out islands were on their own; they would not have been allowed into Key West even if they could get there.

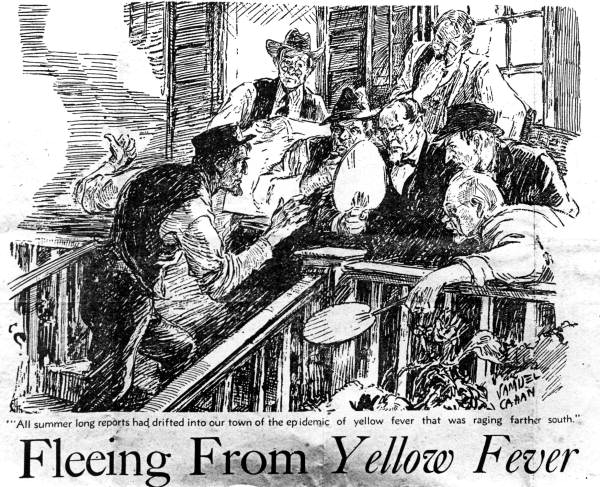

“Drawing related to Yellow Fever – Gainesville, Florida”.

As the aforementioned steamboat went about providing supplies and the mail, many places refused to receive the mail, “We were not permitted to land, and the persons on the bank refused to receive the mail.”

In 1888, the transmission of Yellow Fever impacted transportation. In Callahan, Florida, the residents threatened to tear up the train tracks in their town if the Savannah and Western Railroad continued running through Callahan. Yellow Fever was raging in Jacksonville and Callahan residents feared they were bringing the fever with them as they passed through their town (Huffard).

In September 1899, Key West was under quarantine due to another yellow fever outbreak with over 400 cases. Only those who could prove immunity were allowed to leave the city, otherwise citizens had to leave through the detention camp at Dry Tortugas (“Fever Situation at Key West is Grave”).

Eliminating Yellow Fever

Matt Morgan drawing in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper personifying yellow fever dragging down Florida.

Dr. Joseph Y. Porter, was credited with eliminating yellow fever. The last epidemic in Key West was in 1899. 1320 people were infected. 68 died. 1900 Dr. Walter Reed identified mosquito as cause. In 1905, the last case of yellow fever was detected in Key West, and in 1905 the last case in Florida was recorded (Summers, “Yellow fever”).

A newspaper in 1946 reported concerns of the polio epidemic and recalled the yellow fever epidemic.

“Dr. Joseph Y. Porter, was foremost in the ranks of physicians that fought and conquered yellow fever. Fomes, in those days, was thought to be the major cause in transmitting yellow fever. Whenever anybody died from that disease, the bed, on which he slept, and the bedclothes he used, as well as the clothes he wore when he died were burned. But Dr. Porter poohpoohed that theory. To demonstrate that fomes had nothing to do with transmitting yellow fever, Dr. Porter, in 1892, slept for three successive nights on a bed in the Key West Marine Hospital, in which a man had died of yellow fever. Before it was discovered that the mosquito transmitted yellow fever, the disease was considered as vicious and as insidious as polio is today. Nobody knows the cause of polio; nobody knows where it will strike. As was the case in yellow fever, we must wait now till polio strikes, then fight to save its victim. But, as medical science progresses, the day will come when physicians will learn what is the cause of polio, the nature of its virus, and stamp it out, as yellow fever was stamped out. Polio is a dreadful disease as yellow fever used to be, because, where polio strikes one person now, yellow fever, when at its height, struck 100. It has been many a year since a yellow flag has been seen nailed to a residence in Key West, and the day will come when the red flag of polio will have disappeared.”

(“The Yellow and The Red Flag”)

Works Cited

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Yellow Fever,” http://www.cdc.gov/YellowFever

Diddle, Albert W., “Medical Events In the History of Key West”. Tequesta: The Journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida. Volume 1, number 6. (1946): 14-37. http://dpanther.fiu.edu/dpService/dpPurlService/purl/FI18050900/00006

“Drawing related to Yellow Fever – Gainesville, Florida”. Atlanta Journal, 1930. Florida Memory. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/26663

Dromgoole, John Parham, excerpts from “Dr. Dromgoole’s Yellow Fever Heroes, Honors, and

Horrors of 1878,” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/item/94bbe540c813d363a7a7a0516ca61e22.

“Fever Situation at Key West is Grave.” The Pensacola News. September 20, 1899.

Newpapers.com.

Florida Board of Parks and Historic Memorials. “Historical marker in Key Largo – Monroe

County, Florida” Florida Park Service collection, Series 236, Box 1, envelope 167. Florida Memory. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/116389. 1962

Garrison, William Lloyd, “A letter from William Lloyd Garrison to his son Francis about a fair to

be held to benefit the yellow fever victims in the South, 1878,” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/item/7989d010c73bc2226385dfc36405941a.

Huffard, Scott R. “Infected Rails: Yellow Fever and Southern Railroads.” The Journal of Southern History LXXIX, no. 1 (February 2013): 79–112. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=f432f4f6-8ebc-3645-abbb-61f11a9fe50a

Manatee County Public Library, “Handwritten diary of E.E. and E.B. Johnson and Yellow

Fever, page 62,” USF Libraries Exhibits, https://usflibexhibits.omeka.net/items/show/6683.

Manatee County Public Library, “Handwritten diary of E.E. and E.B. Johnson and Yellow

Fever, page 60,” USF Libraries Exhibits, https://usflibexhibits.omeka.net/items/show/6684.

Morgan, Matthew Somerville, “Matt Morgan drawing in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated

Newspaper personifying yellow fever dragging down Florida”. Florida Memory, circa 1870. http://floridamemory.com/items/show/31518

“OUR KEY WEST CORRESPONDENCE.; The Yellow Fever Its Ravages Among Soldiers and Sailors-Movements of Vessels of War.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1862/09/25/archives/our-key-west-correspondence-the-yellow-fever-its-ravages-among.html?auth=login-google1tap&login=google1tap

“Report of the expedition for the relief of yellow-fever sufferers of the lower

Mississippi,” Digital Public Library of America, 1878. https://dp.la/item/105ae6d30351bd9dd688a66fc073b923.

Summers, Thomas O., excerpt from “Yellow fever,” Digital Public Library of America,

http://dp.la/item/57b34f29fc12259f89a62f1ee298b657

“The Yellow and The Red Flag”. The Key West Citizen, June 12, 1946. Newspapers.com.